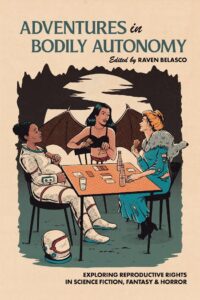

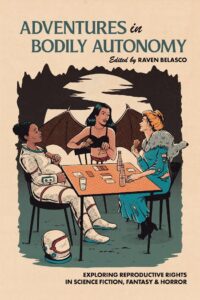

I am excited and proud to have a short story of mine in this anthology, whose proceeds will go to NARAL Pro-Choice America. I will add the press release soon. Pub date: October 16.

I am excited and proud to have a short story of mine in this anthology, whose proceeds will go to NARAL Pro-Choice America. I will add the press release soon. Pub date: October 16.

April 2023

Sabina Spielrein might be considered the patient zero of psychoanalysis. She was predated by several of Freud’s most famous subjects, including Dora, but Sabina’s story of saving and survival is complicated by her relationship with Carl Jung, who, as her doctor, treated her according to Freud’s methods and inspired her to become one of the first female psychoanalysts. She is also representative of a time when treatment for debilitating symptoms of mental illness was measured in months rather than years, although in a more general sense, recovery never truly ends.

Born to a wealthy Jewish family in Rostov-on-Don, a Russian port city near the Sea of Azov, Sabina was raised speaking Russian, German, French, and English. As a child Sabina granted herself a magical power she called partunskraft, which allowed her to know and obtain everything if only she desired it, but it would be a long time before she knew herself.

After several breakdowns, she was hospitalized in the progressive Burghölzli hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. There she was treated for hysteria by director Eugen Bleuler and Jung. (Bleuler is a wash—on the one hand, he coined the term schizophrenia and believed in livable conditions for mental patients; on the other, he advocated their sterilization based on eugenics.) In that it often affected materially privileged Caucasian women, hysteria was the anorexia of its day. Hysteria was not a new concept, but it was the height of fashion when Sabina was diagnosed with it. Its patients made distress visible through gestures, postures, and embodiment, like the silent screen actresses of their time. They were stars of somatization.

February 2023

I just started working on a new novel called The Mnemosynes. No: the truth is I dreamt of it for years. I only now started assembling its pieces with my fingertips.

I lived with this novel long enough for it to become memory before it mazed and runed rough pages.

But I still don’t understand memory. I’ve studied it in literature. I’ve felt its imprints, the just-slipping-into-sleep of it, during rushed hours. I know it’s married to time. After I explained the working plot of The Mnemosynes, in which plots run forward and backward and implode like stars, a friend remarked, “Since memory is what gives us our sense of time, I think it makes sense that memory might manipulate time somehow.”

Memories are—

Timbered, embered, antlered, torn.

Spring’s blossoms, summer’s haze, autumn’s turns, winter’s rage.

Less terraformed than dreams.

Hugged to one’s chest like a child’s legs, when feeling one’s heartbeat is enough.

Scanned and metered, and even when you smirk at the idea that everyone

stresses the same syllable, you still find their poetry.

Kintsugi-ed

Matryoshka-ed.

All the languages I didn’t let myself know.

The cool stream, ribboned and sheened, in which I dip my toes—but I am upside down.

January 2023

In 2016, Andrew Kahn and Rebecca Onion analyzed the gender imbalance in authors of popular history books for Slate and found that roughly three-quarters of them were men. Last year, Johanna Thomas-Curr averred in The Observer that women are dominating fiction in terms of prizes and hype. For readers who are interested in both history and discovering new books by female authors, the solution is simple: explore the past through the following historical novels by women.

Many of the novels below feature real-life characters while some just recreate past epochs and their radical shifts, yet in all of them, women emerge from history’s sidelines. They fight, work, make hard decisions, and strike out to new countries or continents. But in the stories of these nine authors, history is made through private moments of love, creativity, and mourning as much as widely noted acts of bravado and defiance.

December 2022

A dying year promises rebirth. As the Northern hemisphere turns its face away from the sun, we all tilt and tremble, waiting for the new.

This year has schooled me. I spent more time reading than I have in a while, and the books I’ve chosen are only some of those that thrilled me.

Favorite novels

The Books of Jacob by Olga Tokarczuk: Gargantuan and restless, like Poland and all nations.

What Are You Going Through? by Sigrid Nunez: Inspired by a line from Simone Weil’s essay, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View toward God,” this novel attends to the pain of others.

We speak of losing ourselves in both books and forests, but only the latter bodes ill. We pine to escape dark thickets in phrases like “We’re not out of the woods yet.” However, this view of woodlands as sinister and impassible is lensed by colonizers—or, as we call ourselves in Canada, settlers. Fearing an expanse of trees only makes sense if you traffic in cities, industrialization, normalizing, conquering. It only makes sense if you have never been close to the earth.

I’m trying to learn unity and reverence, not fear, in a majestic old-growth forest on the Royal Roads University Campus, which rests on the Xwsepsum and Lekwungen families’ unceded lands on Vancouver Island. Moss emeralds the ground. It reflects not just light but touch; I can feel its cat-fur softness from six feet away. I’m breathing in the smells of mushrooms and pine needles, musk and lichen, and a further June rose.

Botanist and bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer suggests, “When botanists go walking in the forests and fields looking for plants, we say we are going on a foray. When writers do the same, we should call it a metaphoray, and the land is rich in both.” Such a metaphoray requires the writer to remain alert to the terrain, and indeed, my senses quicken as I fathom this forest from the ground up. As I grow, rustling and dappled, at its feet.

I’ve been drawn to the Canadian North since childhood. When I was eight, I saw the movie Never Cry Wolf, based on Farley Mowat’s memoir about researching wolves and caribou decline in the Canadian Arctic. The ice, the space, the sky—I’d never imagined the world could look like a snow globe had broken out of its glass and swallowed half a hemisphere.

The term, “the Canadian North,” is disputed territory. By one definition, it’s synonymous with the triumvirate of Nunavut, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories, whose southern borders more or less run along the 60th parallel. This trio accounts for less than one percent of the nation’s population but two-fifths of its land area. However, Statistics Canada, a government agency, classifies not just these territories but the upper portions of most provinces as northern Canada. Their boundary skirts the Greater Toronto Area and lifts its hem just above the tip of Vancouver Island, where I live. Yet we also speak of the Far North or Canadian Arctic, whose scraps of land thrash in the crushing cold above the Arctic Circle.

In the 1960s, Canadian geographer Louis-Edmond Hamelin coined the word “nordicity,” which delineated the North by latitude but also according to social and geographic determinants like summer heat, annual cold, types of ice, precipitation, population, and economic activity. Of course, global warming is putting pressure on at least the first four. In a few decades, it’s possible that even parts of the Canadian Arctic may not be northern by these criteria.

Abigail, that’s great, but there is a problem with your “there is.” In this case, those two words are an expletive construction, meaning they don’t add value to the sentence. It’s like how “fuck” is a filler word with no real meaning (though it can be a verb too—I guess I don’t have to tell you that!) Be more concise. Why not just say “I have no problem sleeping with strangers”? Save your energy for your other endeavors.

I like the short, staccato sentences to thematize breathless concupiscence. The anaphora created by the repetition of the first-person pronoun is also nice. However, “I can’t be modest” would be a stronger statement. As written, the sudden switch from the definite “I” to the indefinite “one” is problematic. James Thurber wrote of this kind of error, “Rare examples of it still exist and are extremely valuable as antiques, although it is usually unsafe to sit or lie down on one.” Especially in your case, I’d imagine.

Be sure to proofread for dropped words. Microsoft Word won’t catch the missing verb, perhaps “remains,” in this sentence. I find it helpful to read my work out loud. Do you have a cat? Read it to him, a john, whomever!

I’ve been thinking about why we love the art we love. In some of my most formative encounters with creative work, like Lolita, trauma fueled the attraction; in others, such as butoh dance, I was lured by an exotic vibration that turned familiar with time. But for Twin Peaks and The Tale of Genji, two of the works that shaped and soldered me, both trauma and the tension between exotic and familiar fostered my love. And this contemporary television series/movie franchise and this 1000-year-old Japanese novel are both obsessed with doubles.

When I first read The Tale of Genji in college, a friend remarked on the theme of the double. Its protagonist, Genji, loses a forbidden love to taboo (she’s his stepmother) and religion (she takes the tonsure), so he grooms her very young niece to take her place. In the novel’s radical last third, the antihero Kaoru replaces Oigimi, a lover who dies, with her half-sister Ukifune. My friend observed, “Twin Peaks is the same story when it comes to Dale Cooper’s infatuation with Annie,” a young woman and love interest who resembles his dead beloved, Caroline.

1.

My family once knew how to resist great evil.

Less so now. Based on the current generation, we seem unlikely candidates for such heroism. The truth is, we’re average. Some of us have done better than others by whatever metric you might judge a life—career, money, education, length and frequency of marriages, number of offspring. We’ve fallen ill mentally and physically. We’ve divorced and failed in all of the other usual ways. We bicker, ignore, criticize, lie.

But during World War II, from their base at the foot of the Tatra Mountains, a batch of my first cousins, once removed, fought the Nazi regime. They glided to legend the same way they traveled to Christmas Eve’s midnight mass when snow was piled high: on skis.

The Marusarz were poor Polish-Catholic farmers whose children had to quit school after eighth grade to help with chores. But several of them—Stanisław, Jan, and Helena—showed unusual talent as skiers and turned competitive in the 1930s, winning national titles in ski jumping and downhill. Stanisław competed in his first Olympic games in 1932 and participated in four more. For a while, my distant cousins seemed poised to transcend their limited circumstances.

Then, on September 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. After a brief but passionate fight, Poland was occupied by the Germans. The borders were sealed, and Zakopane, where the Marusarz family lived, was declared a closed town. The Tatra Mountains, which rose steeply from its limits and divided Poland from present-day Slovakia, were the one escape route left open. As a precaution, the Germans forced the local citizens to hand over their ski equipment on pain of death. Stanisław, Jan, and Helena chose to keep theirs and use it for good as ski couriers, transporting intelligence and refugees over the mountains and to resistance headquarters in Budapest, in the Armia Krajowa, or “Home Army.”

Anthony Bourdain Lived and Died Around the World (revised)

*I published a version of this essay about four years ago. This is an updated version to commemorate the fourth anniversary of his death.

“There’s something very strange about you, because you look normal,

but it’s all going on inside. Yes, you have got a slight pleading look in your eyes.”

– Nigella Lawson to Anthony Bourdain, “London”

When Anthony Bourdain killed himself, a lot of people on news outlets and social media expressed astonishment that someone so successful would die by suicide. I was stunned that they were stunned. For my part, I’d long been surprised and impressed by the fact that he chose and was able to maintain, for years, a functional life after heroin and crack addiction. To me, that was the unlikelihood.

Yet on some level, I understood other people’s reactions. It wasn’t just because Bourdain had received accolades, amassed wealth, and scored what seemed to many of us the perfect job. We know enough about suicide, or should, to grasp that it is usually not a reaction to one specific event, and even objectively good circumstances may not preclude it. I think the shock was compounded by the fact that Bourdain was always chasing and articulating something so elemental to the human spirit. As a companion in the “Spain” episode of Parts Unknown puts it while they down tripe-spiked tapas: “Sun. Plaza. Guts.” If Bourdain couldn’t be happy with regular dosages of all three, then it seems like we’re all kind of fucked.

I was a fan of Bourdain’s No Reservations series years back but had never watched his more recent Parts Unknown episodes. Shortly after his suicide in 2018, I watched all 64 segments that were on Netflix at the time; this chunk represents two-thirds of the series. I viewed them to enjoy them and to mourn, and also to try to comprehend why Bourdain ended his life—which is, of course, impossible. But it is so tempting to wonder, to treat death as if it has an answer. If it has an answer, maybe there’s a solution too.

Note: A version of this essay appeared on the website, The Ekphrastic Review, in 2019. Because there’s no dedicated link to the piece on the website, I decided to post it here too.

Paul Claudel, the brother of French artist Camille Claudel, had her committed to a mental institution in 1913, just after their father’s death. Although her forms indicated that she had been voluntarily admitted, they were signed by a doctor and Paul, not by Camille.

After about a year, she was moved to another hospital as protection against the advancing German front. But Claudel was a prisoner of war within her own family. Her brother rarely visited and never told her of the death of her loving father, which had allowed him to do what he had likely wanted to do for a long time. Hide away the unmanageable sister who embarrassed him with her unconventional behavior, which included living openly as an artist and having an affair with her mentor, Auguste Rodin.

We’ve entered an era of hyperobjects and microcosms. Plastic fills the ocean, and structures like capitalism are everywhere and nowhere, oppressive and debilitating. But their antidote may be the proliferation of small learning communities, gemlike chips off ivory towers.

The city of Victoria, where I live, is dotted by dovecote-size lending libraries on people’s front lawns. Further up my street, Arts and Crafts houses preface their intricate stories with these mini versions of themselves. The little lending libraries, like the houses, often feature prominent roofs and small-paned windows, and are painted in complementary colors. Bright curlicues and calligraphy invite passersby to take or leave a book. Even when public and university libraries closed down due to COVID-19, these small stores circulated tales and advice, history and dream. Continue reading

When I suffered a life-threatening lupus flare five years ago and lost half my hair, I despaired, especially because many internet articles suggested the loss was irreversible. One blogger said we just had to accept that lupus would take away our hair along with our health.

Fortunately, this is not true! While a patient with discoid lupus, which can cause scarring on hair follicles, might endure permanent hair loss, there’s no reason why someone with systemic lupus erythematosus can’t regrow her hair. I’m wishing that these ten tips for coping with the fallout and growing your hair back better than ever will give help and hope to someone with lupus. Continue reading

These days, the cultural conversation about illness unfolds on social media and kindred outlets. And for about five years before COVID-19, illness was the most glamorous it had been since hysteria in Freud’s heyday. Like with an autoimmune disease, there are periods of remission during which popular culture doesn’t dwell on such downfalls much—but then the focus flares. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to alter our views on sickness, if it hasn’t already. The ill are no longer outliers, and the run-of-the-mill are harder to eroticize. But before its outbreak, celebrities vied on Instagram and other platforms for the title of sickest-but-fairest. Continue reading

Favorite Books (and Plays) 2021

The Shadow King: Ekphrastic terror and haunting music

The Vanishing Half

The House of Breath

Moby Dick

Klara and the Sun: It’s no Never Let Me Go, but Ishiguro makes an interesting attempt to imagine the mind of a non-human

Macbeth, Othello, and The Merchant of Venice: I’m slowly reading through all of the Shakespeare plays that I missed during my first four decades. These three are the last of the unforgivable omissions, with Macbeth’s wintry, witchy poetry my favorite.

Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life: A great companion to . . .

Favorite Films 2021 Continue reading

One of my employers, the University of Victoria, turns 58 this year. Its late middle age coincides with a profound shift in pedagogy, as well as the onset of the post-pandemic period. (It will inevitably be called that though more pandemics are sure to follow in our unsustainable world, making that moniker itself unsustainable.) Two pedagogical trends seem worthy of wider interest in this post-pandemic jungle, especially for those of us living with chronic physical and mental health issues: trauma-informed pedagogy and curricula designed around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Continue reading

This month, I’d like to post links to recent interviews and readings rather than a written piece, partly because it’s still August as I prepare this entry, and I’m feeling late-summer lazy.

First, I want to share a link to an interview I did with the wonderful Rebecca Gagan, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Victoria and the inspired mind behind the podcast, “Waving, not Drowning” (title inspired by Stevie Smith’s poem, “Not Waving, But Drowning”). Rebecca is doing important work by interviewing faculty and staff about their own challenges with mental health as students and how they developed resilience, in the hopes of offering support to current students. But I was also interested in sharing my current and past struggles with mental illness and lupus because I feel that we need a much more open conversation about faculty and staff health at colleges and universities, particularly as we return to campuses impacted by COVID-19. This is especially the case at universities in the United States, which rely more and more on adjunct and associate faculty who may not have any health care coverage through their jobs. Even as we teachers are striving to support our more vulnerable students, our own vulnerability must be admitted and considered as part of the university ecosystem.

Interview with Rebecca Gagan on “Waving, not Drowning” from August 6, 2021: https://www.instagram.com/p/CSPQoKDl2eS/

And here is a link to my reading of the first three sections of the essay, “A Woman in Trouble: My Life and Illnesses Filtered Through Twin Peaks,” published by Witness Magazine in their Spring 2021 issue: https://youtu.be/SxFmGvXrFi4

Given my usual literary preoccupations, which include equity within medical care, the title of this essay may seem like a spoof of my own writings. But it’s not. To me, the topic is deadly serious, as my husband Mark and I are the proud parents of Kuma, a bold, beautiful, loyal, 10-year-old Bengal cat.

Anti-Bengal bias is present, and prevalent, among vets. Bengals are the Borderline Personality Disorder patients of veterinary medicine, immediately stereotyped as “difficult.” It’s true that Bengal cats bear some savage DNA, an atavistic wildness, due to an Asian leopard cat ancestor, generations back. They don’t like to be prodded by strangers and may hiss and fight to get away from a physical exam. But Bengal cats are, in many ways, more domesticated than most domestic cats. Kuma waits for Mark by the door when he goes out, a feline Hachiko. He happily walks on a leash. He is gentle, if cautious, with strangers who want to pet him, including the many children who flock to him during our strolls. Continue reading